The gap between what academics do and what those outside of the academy think they do is enormous. The mysteriousness and elite status that universities enjoy may actually serve to undermine the very values of inquiry and education that it seeks to promote. In this second in series of posts on academic life, I take you behind the curtain of Academic Land of Oz to illustrate what life for at least one professor looks like.

‘Cause you’re working

Building a mystery

Holding on and holding it in

Yeah you’re working

Building a mystery

And choosing so carefully- Sarah McLachlan, Building a Mystery, from the album Surfacing

The academic world has been my home for my entire adult life and one that I helped to build and shape along with my peers with the aim of making a contribution to our collective knowledge, the education of (mostly) young professionals, and hopefully enriching all of our lives along the way with insight drawn from research. This is what the public thinks happens in universities and, to a large extent, they are right. But the way this is done, the roles people play, and the manner in which the academic system is designed and operates is as much of a mystery you will find in our society. But perhaps its time to (un)build it**.

And unlike the Wizard of Oz, this mystery does more to harm those both building it and experiencing it from the outside. How? In part, because times are changing quickly and public institutions along with it. When times are tight, there is little appetite to support professors sitting in their offices, thinking deep thoughts, doing research that has tangential value for society, teaching badly to undergrads and only to small groups of grad students, and taking four months off in the summer and three during the December holidays.

The first part of the problem is that this perception is widely off the mark from reality.

The second part is that universities seem to be doing a poor job of correcting this perception.

For starters, universities are investing a lot less in faculty than people think. In my six years, my university itself only picked up only a small portion of my salary. The rest was through a philanthropic donation, salary awards I earned from both government-funded research programs (e.g., the Canadian Institutes of Health Research), contracts with community service groups, or sometimes from grants. Unlike other countries, Canada doesn’t have a system where investigators can easily draw a salary from the operating grants they receive. Thus, I could afford research assistants, equipment and travel, so long as I didn’t get paid.

To cover this, I had to get separate career awards to pay for my salary and as these awards typically covered less than 50% of my wage, I needed multiple revenue streams at the same time. This meant writing 2-3 times the number of grants that a tenured faculty would have to write. To make matters worse, there are a lot more people in my position than there are tenured faculty so the competition was and is stiff.

In the current CAUT Bulletin, Tom Booth writes about this further in the context of academic freedom and the US system:

It is disturbing to note that only 41 per cent of faculty members in universities in the U.S. are tenured or tenure stream. The majority of those will be retiring in the next 10 years and unless the current trend to replace tenured academic staff with non-tenure track appointments is reversed, the next decade will likely see tenured faculty representing only 20 per cent of American university teaching and research staff.

Earlier research by Harold Bauder (PDF) on academic labour segmentation in Canada found, among other things:

In Canada, academic labour has been depreciating over the previous decades. For example, faculty salaries declined relative to total expenditures of universities, from more than 31 percent in the late 1970s to roughly 19 percent in 2004 (CAUT, 2006, 4). In addition, the faculty-student ratio at Canadian universities has changed. While in the 1992-1993 academic year there were on average only 18.8 full-time students for every full-time faculty member, eleven years later there were 23.7 (CAUT, 2006, 51).

For more on the problematic faculty math in Canada, check out the CAUT’s report on the state of university teaching (PDF).

But the research side of the equation isn’t faring much better. Last February I profiled the declining state of things in the United States, which is mirroring Canada. Scientists Johannes Wheeldon and Richard Gordon recently pointed this out in a column in the Huffington Post, stating:

The role of research funding to an academic’s career has never been more important, and yet there is an emerging consensus that the way we organize our system of research grants is broken. While concerns about Canada’s model of research funding are longstanding, in recent years they have become increasingly stark. These include perpetual underfunding, charges of bias, and an over-reliance on the peer review system, which favours orthodoxy over innovation.

In short: if you’re a young researcher your share of the funding pie is smaller than ever. If you want to innovate, your prospects are even worse.

Yes, but what about academic freedom? That does exist, for now. In all my years at my university my boss (the Chair or Director) came to visit me only a handful of times. No one checks when I arrive or leave, nobody even cares if I work from home or a desert island. As long as I show up for my teaching duties, respect academic procedures, and continue to produce good research, the university system doesn’t much care what I do with my day-to-day activities. That is a real blessing and supports creative thinking about big problems.

Yet, while I could sleep in almost any day, I never did. I could take a long weekend anytime, but instead was in the office. Visiting a cottage? Sure, so long as there was Internet access and plugs for a laptop. See the world! — just make sure you keep on top of your email. Family time is wonderful as long as there’s time to write before and after. My average workweek was 90 hours for the past two years. And while work does inspire me, too much of anything is not good for long periods of time. Oh yes, and did I mention that I study health promotion? The power of social norms, and of what Pierre Bourdieu calls habitus, is akin to the Death Star‘s tractor beam, only you don’t see it; it’s deep within us.

None of these were enforced activities, but they are the norm. My faculty colleagues — young and old, tenured or not — work long hours all year. The system is set up for it. For example, the Tri-Council grants in Canada — SSHRC, CIHR, and NSERC – and many of the major health charities that fund research all have deadlines that require registration (pre-proposals) at times between August 15th and October 30th, which happens to coincide with things like: 1) summer vacation for most North Americans and Europeans (in August and the months before when you organize the research plan), 2) start of classes and the academic year, 3) orientation of new students, and 4) student awards and bursaries (for which we serve as referees to write letters of support). Just try and get a date for anything longer than lunch with an academic doing research during this time.

Grading? Our exams and papers are due at my institution on December 21, which means Hanukah, Christmas, Kwanzaa, and New Years Day are all grading holidays. Pass the gravy on this turkey.

And we are the ones who invented this system!

None of what I am writing is meant to garner sympathy for me personally. I made these choices in my career with a hope it would lead to something good for the world, myself and those I care about. Sometimes I succeeded and others not, but they were my choices that I live with, whether wise or not. What I am doing is trying to paint the picture for others about the environment that I and other faculty and staff like me live in every day. This is not the idyllic life that the public thinks it is. And while the professor is still among the most respected professions out there, it will fall flat if times get tight and people are looking for more for less and we faculty are seen (misguidedly) as having more while others have less.

But what about pay? That’s a tricky one. I get a wage that I have no complaints about in absolute terms. I make well above the Canadian average, but not something that is anywhere close to being indexed to education. Considering I have 16 years of post-secondary education (education that I paid to have), I could have done a lot better going into other fields. But as a wise colleague of mine once said about pay in professor-dom: “you won’t get rich, but you’ll never be poor” . That counts for something.

At the same time, on an hourly basis, my pay goes downhill. And at some point, time becomes worth far more than anything I have to offer financially. I also have the support to spend money on my job. Indeed, teaching supplies, continuous learning, staff rewards (and continued education for them), and the incidentals from the job cost money for which there are few mechanism to pay from in most traditional centres. They come from somewhere and that’s the faculty member’s pocket, just as elementary and secondary school teachers often pay for school supplies. We believe so strongly in what we do we’ll do it without recognition or compensation.

We are a tribe that is as foreign to the public as the San people in Africa were to the first European explorers. But like a tribe we have behaviours that are not always pro-social.

Academia has been considered gang-like in its behaviour:

Just as members of street gangs earn most of their livelihood from theft, academics gain most of theirs from careers. Being a member in good standing of a gang and a supergang is crucially important for advancement of one’s career. There is little chance of advancement in the academy without hard work, but flaunting membership in gang and clan can certainly supplement or even substitute for talent and intelligence. Clearly and repeatedly showing one’s loyalty to these groups can be most helpful in obtaining research grants and acceptance of publications, twin lifebloods of the academic career. – Scheff, T.J. (1995), Academic gangs. Crime, Law, and Social Change 23: 157-162.

It is a strange space to be in. Alien.

While I don’t particularly like the system we’ve created, it is what it is — today. But it can change if we — all of us — stop and pay attention to what it really is and work to make it what we want it to be. Well established institutions are hard to change because the practices within them are so deeply entrenched in a culture that is often accepted as is.

As this series unfolds, I’ll explore some more of these themes in detail.

The message to my fellow academics is this:

The modern university system has a lot of problems, yet our mandate and potential to contribute to the world through our research, teaching and social consulting is as big and needed as ever. Society needs us when we’re at our best, but we are doing more to undermine our best at our peril. We need to fix the system now otherwise forces beyond ourselves will force the changes on us in ways that may not be conducive to good scholarship, equity, and effective public service.

For those who like the system as it is, let me leave you with this quote from Guiseppe di Lampedusa’s book, The Leopard:

If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change..

I don’t think we want things to stay as they are. But, we do want some things to stay the same.

This is the latest in the Alien Shores series of reflections on life in academia from one who is about to leave it.

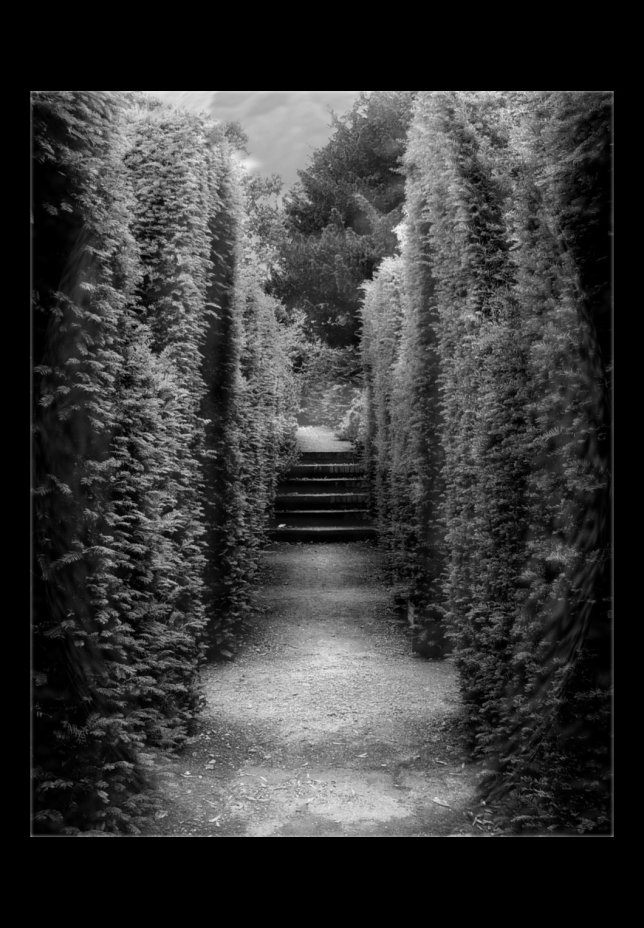

* Photo Mystery by UKTara used under Creative Commons Licence from Deviant Art.

** and yes, I know that un-building is not correct use of the English language. But deconstruct, take down, demolish or pull apart don’t work here. I am using my academic privilege to make words up ![]()

Unravel the mystery and crank up Sarah McLachlan and think about what these words mean for our business…

Sarah McLachlan “Building a Mystery”: excerpt

You live in a church

Where you sleep with voodoo dolls

And you won’t give up the search

For the ghosts in the halls

You wear sandals in the snow

And a smile that won’t wash away

Can you look out the window

Without your shadow getting in the way?You’re so beautiful

With an edge and charm

But so careful

When I’m in your arms[Chorus]

‘Cause you’re working

Building a mystery

Holding on and holding it in

Yeah you’re working

Building a mystery

And choosing so carefully

Filed under: Education & Learning, research, Science & technology Tagged: academia, academic freedom, education, faculty life, innovation, research, teaching, university